https://www.blouinartinfo.com/news... more >> This year marks the 95th birthday of the renowned figurative painter Philip Pearlstein. To celebrate the occasion, the Galerie Templon in Paris is holding an exhibition of the American artist’s work, on show until July 20. The 14 oil paintings that constitute the exhibition span nearly 50 years of Pearlstein’s career, with recent works from 2018 alongside earlier paintings dating as far back as 1969.

https://www.blouinartinfo.com/news/story/3679729/philip-pearlstein-at-95-at-the-galerie-templon-paris

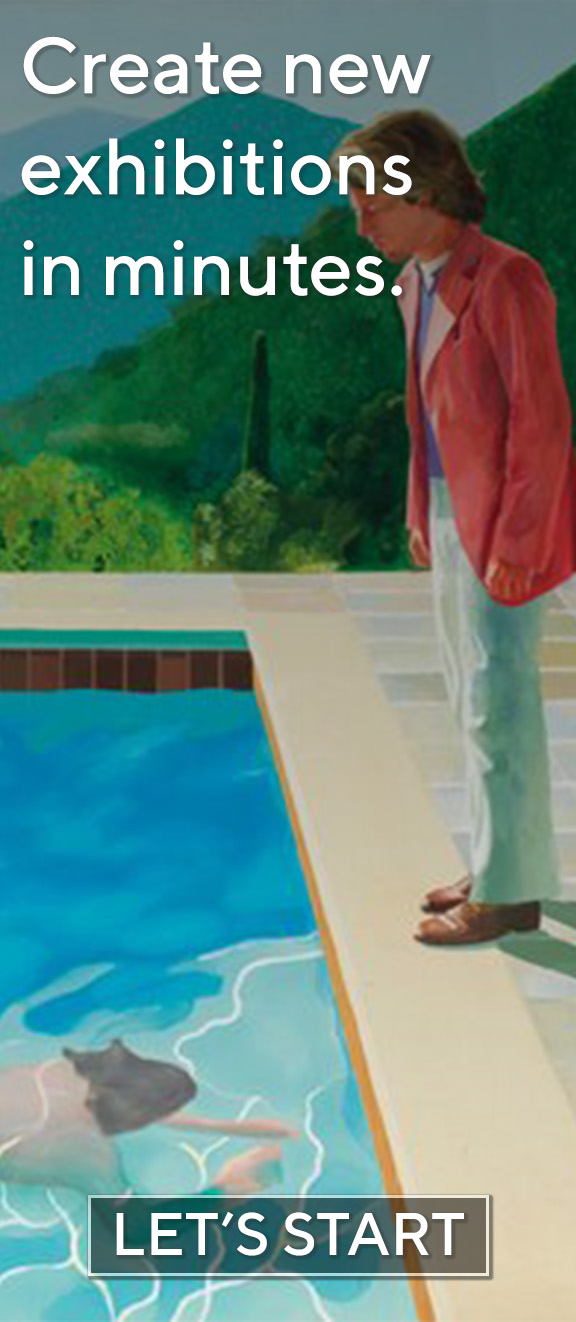

Rather than trace the evolution of the artist over the years, the exhibition is striking in that it shows an overwhelming coherence to his body of work. Pearlstein’s paintings depict nude models, drawn from life, positioned among an eclectic assemblage of unusual and exotic props: African masks, woven rugs, drums, statues and chairs from just about every imaginable culture and epoch. As a Realist painter, Pearlstein has impressive technical skill. His subject matter often seems dictated precisely by the technical challenge it offers him — the harder the better. A yoga ball; a transparent, inflatable chair; and a curved stainless-steel armchair reflecting a patterned rug beneath it – all give the artist ample opportunity to flex his painterly muscles.

Although Pearlstein has rendered both male and female models over the years, all but one of the models in the current Templon exhibition are women. As visitors move from one picture to the next, they are met with the same impenetrable gazes that are characteristic of Pearlstein’s work. Many of the women are asleep, their faces expressionless; those that are awake look listlessly out of the frame. In contrast to a long history of erotic representations of female nudes, Pearlstein’s models are not sexualized. Their bodies are not offered up to the viewer’s gaze, but are positioned with a strange sort of nonchalant agency.

One of the most destabilizing aspects of Pearlstein’s paintings is how the models resist any trace of interiority. At a push, one might read boredom, apathy or resignation on the blank slate of a model’s face, but the adjectives never quite stick. Symbolism, metaphor and story-telling are equally absent. In two paintings exhibited in the show, the models’ faces are concealed by animal masks. The viewer might be tempted to read this as a self-referential comment on the erasure of personhood. But this desire for signification would be projected on a painter who very explicitly rejects it.

It is unusual it is to see a Realist depiction of a human subject that does not also attempt to render that subject as more than just the sum of his or her physical form. For Pearlstein, the body becomes an assemblage of skin, muscle and bone, to be translated faithfully into oil, an object among objects. His paintings focus on the physical properties of the bodies, on how these human bodies share the frame with the inanimate props around them, and on the unlikely formal patterns to be found between the two. In “Two Models with Swan Decoy and Carved Garuda Figure” (2013), the curve of the model’s folded leg and foot traces the same arc as the neck of a swan sculpture and the shadow it casts on the model’s buttocks. Her ribcage protrudes with the same curvilinear form as the carved wooden claw of the sculpture behind. Walking around “Philip Pearlstein at 95,” one revels in the artist’s attentiveness to form and composition, and in his mastery of the two.

When asked about his work, Pearlstein once said “As a rose is a rose, so my paintings of models are paintings of models.” In this reference to Gertrude Stein’s famous phrase “A rose is a rose is a rose,” the artist aligns himself with a cerebral form of Modernism that, in its resistance to narrative and interiority, limits its capacity to move the viewer. This is borne out in “Philip Pearlstein at 95,” where the paintings are unlikely to speak on an emotional level or to leave the viewer with much to reflect on afterwards. Nevertheless, the artist’s abundant technical ability, the immediate intrigue of his unusual compositions, and his subversion of more conventional forms of Realist painting, make for an idiosyncratic configuration that will no doubt earn him his place in the history of American art.