“Photographer as Sculptor, Sculptor as Photographer” was on view from 10 April 2025 to 24 June 2025 at Bruce Silverstein Gallery, New York.

In the contemporary art world, where medium-specific boundaries are increasingly blurred, Photographer as Sculptor, Sculptor as Photographer emerges as a timely exploration of the interplay between two distinct yet deeply interconnected artistic practices. On view at Bruce Silverstein Gallery in New York, the exhibition challenges the historical hierarchy that has often placed sculpture above photography, asserting the latter’s equal capacity for abstraction, materiality, and spatial presence. The show is structured thematically rather than chronologically, drawing together works from the mid-20th century to the late 1970s, highlighting how artists like Aaron Siskind, Auguste Rodin, Henry Moore, and André Kertész used the camera not merely as a tool of documentation but as a means of sculptural expression.

At its core, the exhibition interrogates the idea of form—how it can be captured, abstracted, or even invented through the lens. Curatorially, this is achieved by juxtaposing photographs with physical sculptures, revealing how each artist approached the body, space, and texture with a dual sensibility: photographers thinking like sculptors, and sculptors composing like photographers. The result is a dialogue that transcends medium and era, suggesting that the creative impulse behind shaping form is universal, whether working with stone, metal, light, or shadow.

One of the most compelling works in the exhibition is “L’Éternel Printemps (Eternal Spring), 2nd reduction” by Auguste Rodin—a bronze sculpture depicting two entwined figures locked in a tender embrace. Rendered in smooth, flowing lines, the figures seem to emerge organically from the material itself, their forms blending into one another in a gesture of both protection and vulnerability. What elevates this piece within the context of the exhibition is not only its formal elegance but also the way it invites comparison with Rodin’s own photographic practice. Though no direct photographs by Rodin are included, curator Bruce Silverstein notes in his interview how Rodin supervised the photographic documentation of his works with such precision that these images became aesthetic objects in themselves. In this light, Eternal Spring becomes more than a sculpture—it is a meditation on touch, movement, and visual translation across media.

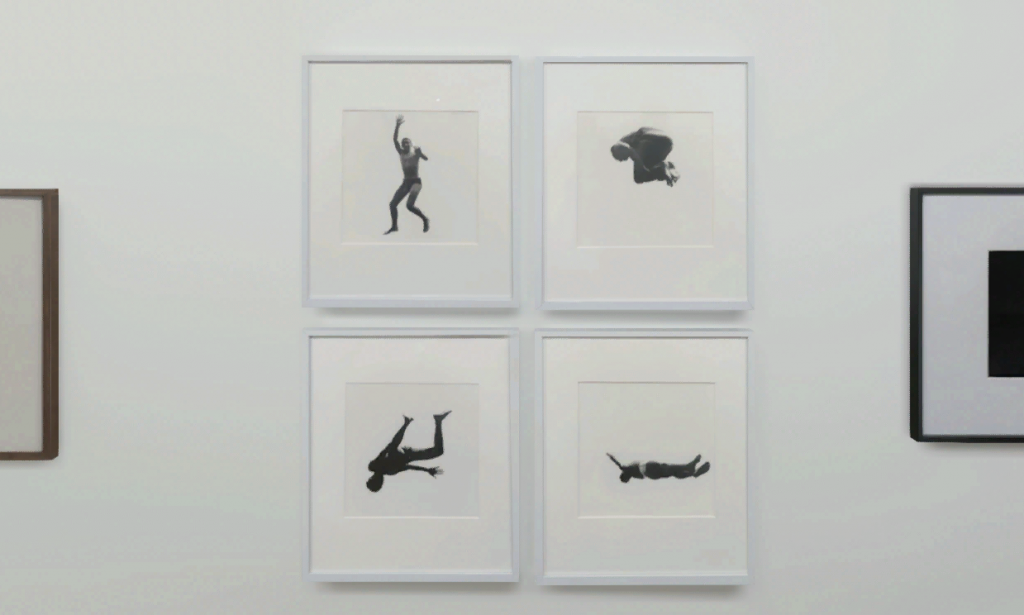

Aaron Siskind’s “Pleasures and Terrors of Levitation #36” (1956) offers a stark contrast in medium but a parallel intensity in form. This gelatin silver print captures a figure mid-air, suspended in a moment of grace and motion. The subject’s silhouette is sharply defined against a white background, creating a dramatic interplay of light and shadow that echoes the sculptural emphasis on contour and volume. Like Rodin, Siskind was deeply invested in abstraction—not through material manipulation but through framing, focus, and composition. As Silverstein notes, Siskind had to fight for recognition within the Abstract Expressionist circles, mounting his prints on stretcher boards to make them “come off the wall like a wall relief.” His inclusion here underscores the exhibition’s thesis: that photography can function as a sculptural act when it transforms the ephemeral into the monumental.

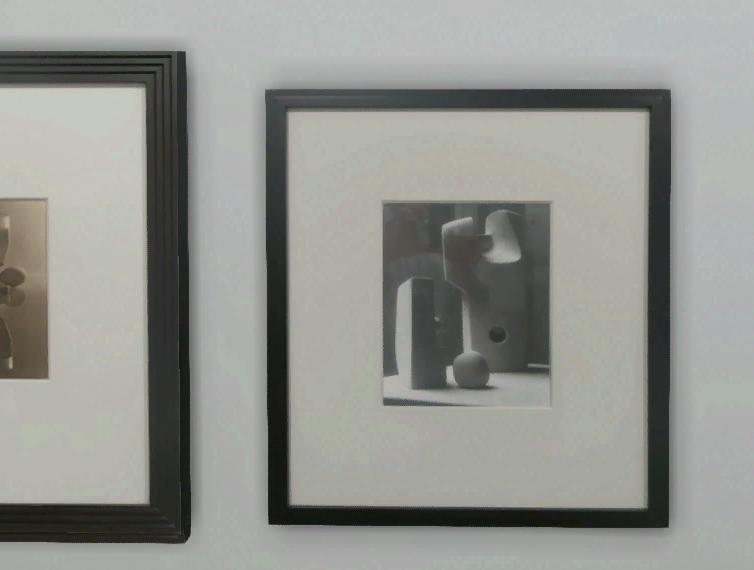

Henry Moore’s photograph of his own sculpture “Three Forms” (1957) further complicates the relationship between maker and medium. Moore, known for his large-scale organic abstractions, used photography to reframe his maquettes, often placing them outdoors to manipulate scale and atmosphere. In this image, the small bronze forms are positioned in a natural setting, their shadows elongated by low sunlight, giving them an imposing presence. Moore’s photographic eye turns what might be a preparatory study into a standalone artwork, emphasizing the play of negative space and surface texture. This approach aligns with broader modernist tendencies to blur the line between process and product, sketch and final form.

Finally, “December 15” (1979), a color SX-70 Polaroid by André Kertész, serves as a lyrical coda to the exhibition. Featuring two stylized glass figures facing each other, connected by a translucent green sheet and anchored by a blue marble, the composition is minimal yet emotionally resonant. Kertész, long known for his poetic approach to everyday subjects, uses the immediacy of the Polaroid format to create a tableau that feels both sculptural and ephemeral. The reflective surfaces and soft gradient background evoke a sense of stillness and introspection, reinforcing the idea that photography can generate its own kind of sculptural presence—one rooted in temporality and light rather than mass and material.

By challenging traditional divisions between disciplines, this exhibition signals a new direction—one that embraces a fluid, interdisciplinary approach across all mediums of art.

The strength of Photographer as Sculptor, Sculptor as Photographer lies in its ability to reframe familiar works through a new conceptual lens. By positioning photography not as a secondary medium but as a parallel practice to sculpture, the exhibition dismantles outdated hierarchies and highlights the shared language of form, gesture, and abstraction. It invites viewers to reconsider the photograph not just as a record of three-dimensional work but as a site of creation in its own right.

This thematic clarity is enhanced by the thoughtful selection and arrangement of works, which allow for subtle visual rhymes and contrasts across decades. From Rodin’s tactile embrace to Siskind’s levitating bodies, from Moore’s reimagined maquettes to Kertész’s meditative Polaroids, the exhibition constructs a narrative of artistic innovation that transcends individual authorship. It is a quiet but powerful assertion of photography’s place in the canon of modern art—not as a derivative medium, but as a sculptural force in its own right.

If there is a cultural touchstone that resonates with this exhibition, it might be the 1980s music video aesthetic—particularly David Bowie’s Ashes to Ashes , where fragmented imagery and shifting perspectives create a sense of sculptural abstraction in motion. Like Bowie’s work, this exhibition thrives on ambiguity, inviting viewers to question where one medium ends and another begins. In doing so, it reaffirms the enduring relevance of artists who dared to cross disciplinary boundaries, and the curators who continue to champion their vision.