“What Work Is” by Şerban Savu was on view from April 20 to November 24 2024 at the Romanian Pavilion at La Biennale di Venezia 2024

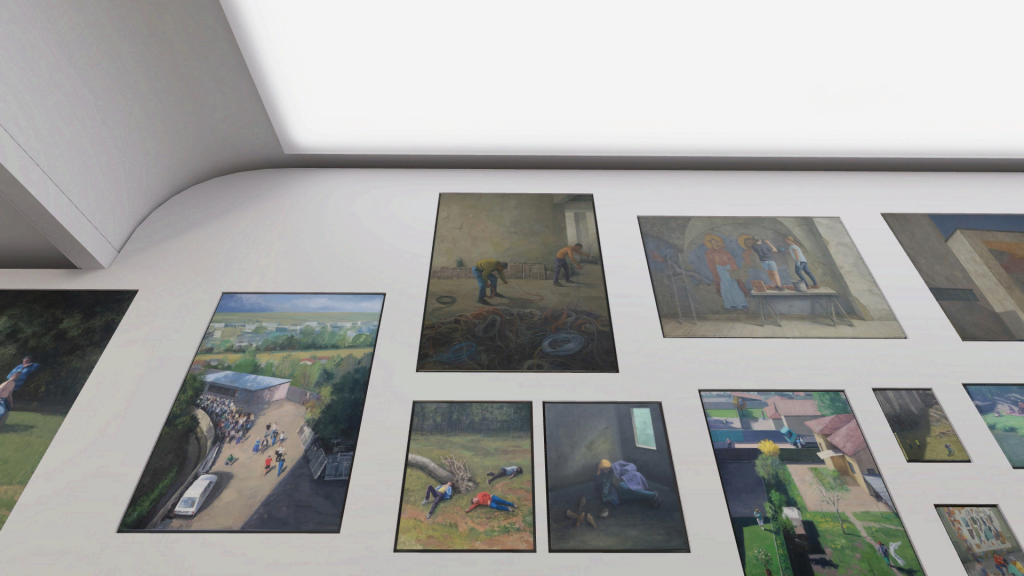

In a time when labor’s meaning grows ever more ambiguous, “What Work” Is, Șerban Savu’s 2024 exhibition for the Romanian Pavilion at La Biennale di Venezia, speaks in the subdued tones of inertia. Curated by Ciprian Mureșan, the exhibition spans the Romanian Pavilion in the Giardini and the New Gallery of the Romanian Cultural Institute, weaving a visual narrative through approximately 40 paintings and mosaics. Rather than dismantling Socialist realism, Savu rearranges its rhetoric—once revolutionary, now weary—into tableaux of ambivalence, where workers linger between productivity and pause. The pavilion becomes a site of suspended action, populated by disoriented figures that mirror the broader societal crises of post-industrial malaise, migratory estrangement, and ideological drift. These paintings and architectural models offer a reinterpretation of Socialist aesthetics—less monument, more murmured doubt—set in counterpoint by Atelier Brenda’s textual interventions on the façade and lobby, which reimagine labor as non-ideological propaganda.

Șerban Savu, born in 1978 in Sighișoara and based in Cluj, is a leading figure of the Cluj school. Known for his figurative, meticulously composed canvases, Savu captures moments where work is neither glorified nor negated, but suspended in quiet scrutiny. With a background that includes study in Venice and decades of exhibitions across Europe, Savu resists dramatic gestures in favor of subtle contradictions. His practice centers on contemporary Romanian life—its ironies, gaps, and ordinary moments—with a palette and composition that evoke both the precision of socialist art and the fog of post-socialist reality. In Savu’s world, work is never finished, and rest never fully restorative.

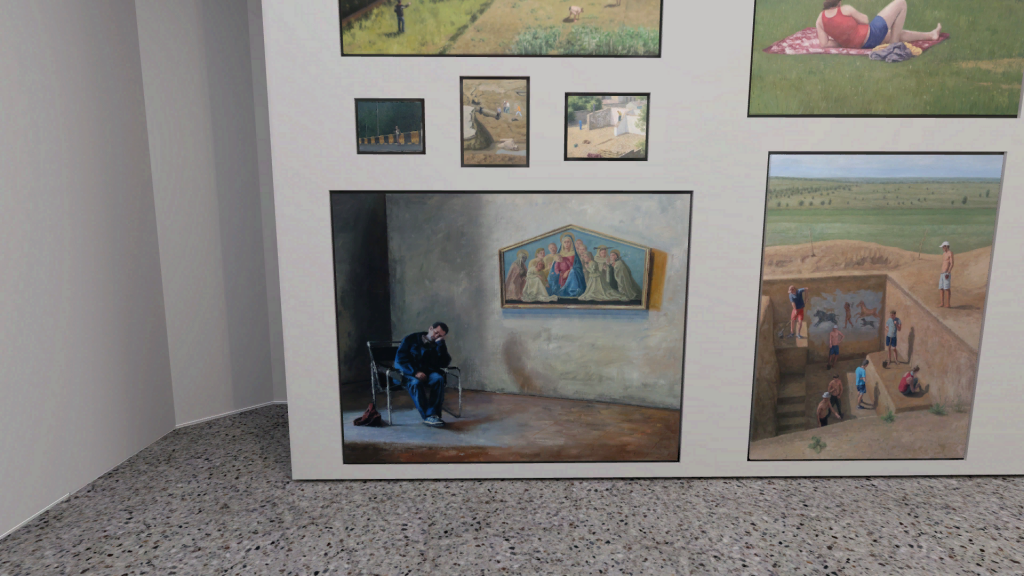

In “The Guardian” (2015), a museum guard sleeps slouched in a Marcel Breuer armchair before a Renaissance painting of the Virgin Mary. The scene is one of layered incongruity: vigilance surrendered, religious imagery glowing in contrast to the sterile walls. Here, Savu allows a slippage between rest and revelation. As Mihnea Mircan notes, the man’s sleep becomes a kind of unconscious devotion, a dream-state interpretation of the sacred. The painting’s quietude masks a deeper social metaphor: a wearied workforce caught between duties they no longer believe in and images that promise a spiritual protection long since eroded. This canvas becomes an emblem of the exhibition’s thesis—where labor’s meaning dissolves, and inactivity becomes a strange kind of agency.

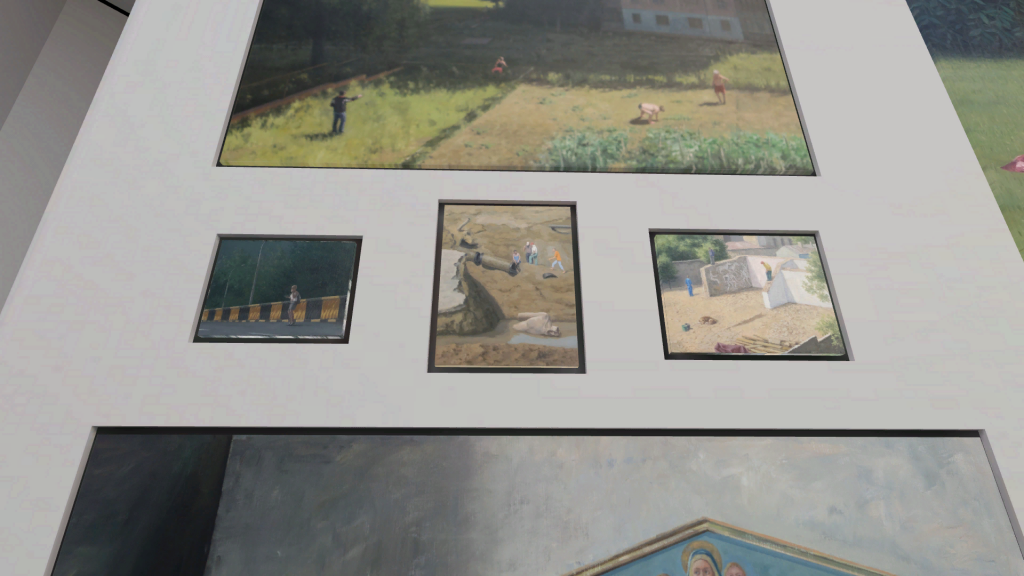

“The Old Pipe” (2021) captures a group of workers gathered around a buried object—possibly a statue fragment—amid exposed pipes and earth. There’s an archaeological feel to the composition, as though digging into the debris of forgotten ideals. The ambiguity of their task mirrors the societal confusion Savu paints throughout: is this maintenance, discovery, or merely futile repetition? The labor here is stripped of heroic sheen; instead, it’s quiet, puzzled, and curiously intimate. As viewers, we witness not just an excavation of ground, but of memory and identity—where Socialist realism’s grand promises have given way to modest, muddied truths.

In “Father and Son” (2021), two men disentangle a maze of cables in a half-built environment. The gesture is Sisyphean—are they organizing or adding to the chaos? The relational dimension, suggested by the title, reframes the scene: this is not just physical labor but the symbolic sorting of generational trauma. As Mircan writes, the cable becomes a metaphorical neural network, a coiled lineage of unspoken histories and ideological burdens. The painting refracts the exhibition’s theme into a more intimate register, where work becomes a medium for communication between father and son, even when the task itself remains opaque.

In “Capriccio with Fountain” (2023), a group of boys gathers around a well amid the ruins of a collapsed architectural space. The sky is bright, the mood light—yet the backdrop suggests abandonment. Savu stages a capriccio, a classical term for architectural fantasy, where the fragments of old structures become sites of improvisation. Here, play emerges within decay, as if the next generation inherits not ideology, but space to imagine anew. This piece rounds out the exhibition’s vision: not with closure, but with a cautious optimism nestled within the ruins of conviction.

“This is not just physical labor but the symbolic sorting of generational trauma—an attempt to untangle inherited histories.”

In“What Work” Is, Savu delivers a quiet yet powerful interrogation of labor as a hollowed ritual, a shared myth in slow collapse. The exhibition doesn’t propose a solution—it renders the impasse with grace and precision. For visitors willing to linger in the interstices of work and rest, ideology and ambiguity, Savu offers a profound viewing experience. His images do not shout; they murmur, in tones as faded and enduring as the landscapes they depict.