Wolfgang Tillmans’ “Installation (1992–2018)” was on view in 2018 at the Albertinum, Dresden.

In an era marked by political fragmentation and cultural dissonance, Wolfgang Tillmans’s “Installation (1992–2018)” at the Albertinum in Dresden arrives as both a contemplative retreat and a resonant call for reflection. The exhibition is not merely a retrospective but a carefully constructed narrative that spans nearly three decades of Tillmans’ photographic practice, weaving together personal intimacy, historical trauma, and abstract experimentation. Housed within the historic walls of the Albertinum—home to both Romantic masterpieces and contemporary provocations—the installation forms a dialogue between eras, inviting viewers to consider how images shape memory and meaning. Rather than a linear chronology, Tillmans offers a thematic constellation, where each photograph resonates with others across time and context. This curatorial approach underscores his belief that photography is “an interpretation of the world,” not a neutral record. In Dresden—a city deeply scarred by war and rebuilt through collective will—the emotional and philosophical weight of the exhibition finds fertile ground.

A Humanist Eye: The Art of Wolfgang Tillmans

Wolfgang Tillmans emerged in the 1990s as a defining visual chronicler of youth culture, capturing the fluid identities and unguarded moments of European nightlife with a poetic sensitivity. But he has always resisted being labeled a documentarian; instead, he positions himself as a Bildermacher, or “picture-maker,” whose work interrogates the very nature of image-making. His practice extends beyond traditional photography into abstraction, spatial installation, and conceptual framing. From intimate portraits to camera-less chemical experiments, Tillmans treats all subjects with equal visual and philosophical rigor. As he once stated, “I take pictures, in order to see the world.” This ethos underpins “Installation (1992–2018)“, which presents 23 works arranged in a non-hierarchical, site-specific manner—an evolving conversation rather than a static display.

“Lightning II”(2002) immediately commands attention with its sweeping drama—a storm-lit sky split by jagged bolts of lightning over a darkened treeline. Rendered in rich tonal contrasts, the image channels the Romantic tradition while asserting its modernity through scale and clarity. It evokes Caspar David Friedrich’s sense of the sublime, yet Tillmans reframes it through the lens of contemporary environmental and existential anxieties. The photograph functions as both spectacle and metaphor, suggesting nature’s uncontrollable force and humanity’s fragile place within it.

“Silver 105” (2012), by contrast, strips away narrative entirely. It is a monochromatic field of soft turquoise, interrupted only by faint specks—possibly raindrops or dust—on the surface. Part of Tillmans’ abstract series, this large-scale print framed in white transforms photography into a meditative experience. Without subject or scene, the viewer is left to contemplate texture, light, and impermanence. It challenges the documentary impulse, offering instead a quiet, almost painterly introspection that echoes Yves Klein’s explorations of color and space.

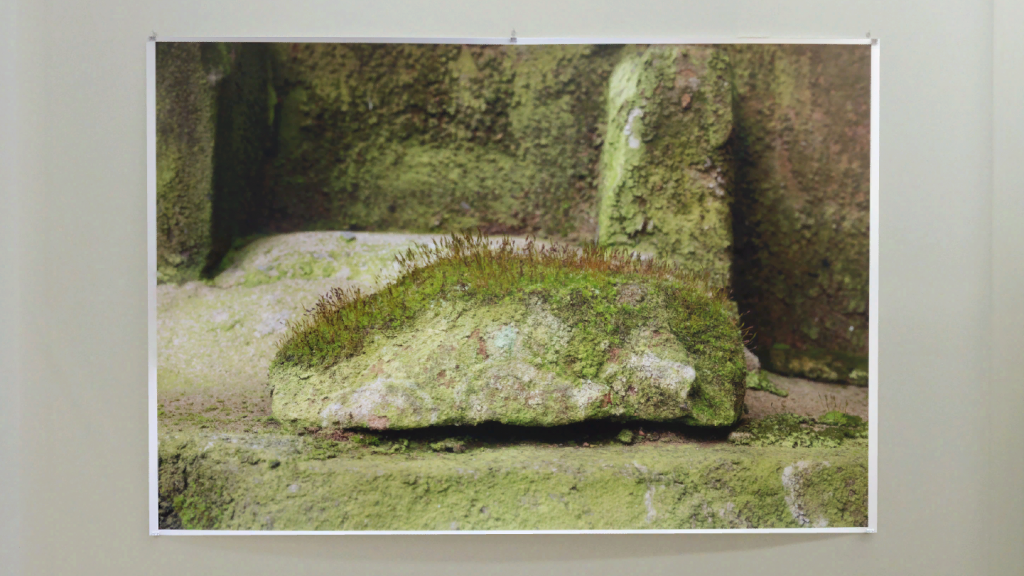

“Coventry Cathedral” (2018) is a close-up of moss-covered stone, a fragment of a ruined structure rendered in lush green tones. The image is both specific and universal—part of a broader exploration of reconciliation inspired by Benjamin Britten’s “War Requiem” . Here, Tillmans merges the historical and the organic, showing how nature reclaims human-made devastation. The cathedral ruins become a symbol not just of destruction but of renewal, echoing themes central to Dresden’s own postwar rebirth.

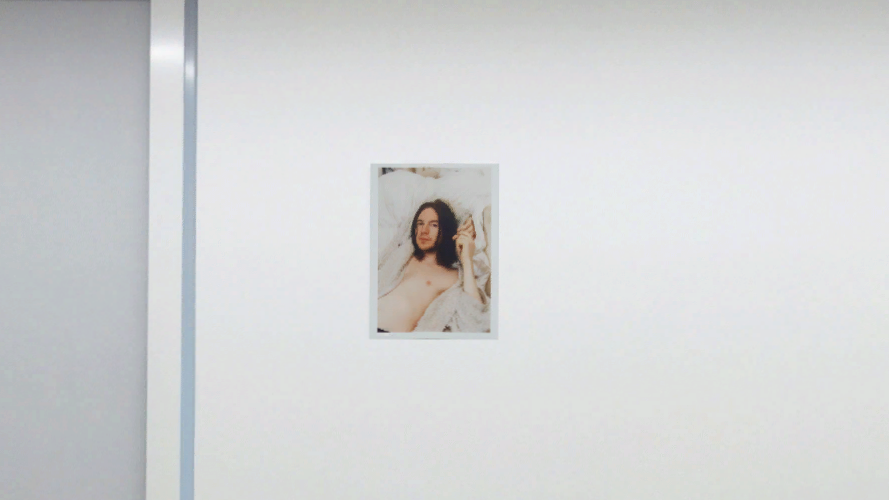

“Chris Cunningham” (1998) brings us back to the human scale. A small, unframed portrait shows the eponymous filmmaker lounging in bed, partially draped in a faux fur robe, gazing directly at the camera. Intimate yet composed, the image blurs the line between casual snapshot and formal portraiture. It reflects Tillmans’ early reputation as a photographer of queer and creative communities, capturing vulnerability without sentimentality. The work anchors the exhibition in personal relationships, reminding us that Tillmans sees the individual as inseparable from the broader cultural moment.

Curatorial Vision: Thematic Weaving and Spatial Poetry

The curatorial strength of “Installation (1992–2018)” lies in its refusal to dictate a singular reading. Instead, the arrangement invites viewers to navigate a web of associations—between the ruin and the rebuilt, the intimate and the historical, the representational and the abstract. Tillmans himself designed the installation, positioning photographs at varying heights and formats, some pinned directly to the wall, others framed with precision. This mix of presentation styles reinforces his democratic view of imagery, where a Polaroid-like print shares space with a large-format archival photograph. Supplementary texts, including excerpts from the “Litany of Reconciliation” , deepen the exhibition’s meditation on guilt, memory, and peace-building. The result is not a museum-style didacticism but a layered encounter that rewards careful looking and emotional openness.

Tillmans creates a visual symphony where the mundane becomes monumental, and history feels urgently alive.

What makes “Installation (1992–2018)” particularly compelling is its ability to balance the immediacy of the photographic image with the long arc of history. In Dresden—a city intimately tied to wartime destruction and post-Cold War solidarity—Tillmans’ focus on Coventry and Dresden’s shared histories gains added poignancy. His photographs do not offer easy resolutions but instead encourage viewers to sit with complexity, to see how time grows over the past, as moss covers stone. This is not just an exhibition about photography; it is an exhibition about how we live with images, how they shape our understanding of self, society, and the passage of time.

For those seeking art that engages both intellect and emotion, “Installation (1992–2018)” delivers with quiet intensity. Tillmans reminds us that even the most fleeting moments—of joy, sorrow, or stillness—can resonate across decades when framed with care and vision.