Susan Hensel Gallery

June 15-August 15, 2021

Artsy.net/susan-hensel-gallery

From the Center: Linda King Ferguson’s Dimensional Paintings

Lin... more >> At the intersection of painting and object making, the restrained images of Linda King Ferguson rely on the co-properties of textiles and painting processes. She thoughtfully stains, paints front and back, creates layers while cutting away and peeling forward the images.

Susan Hensel Gallery

June 15-August 15, 2021

Artsy.net/susan-hensel-gallery

From the Center: Linda King Ferguson’s Dimensional Paintings

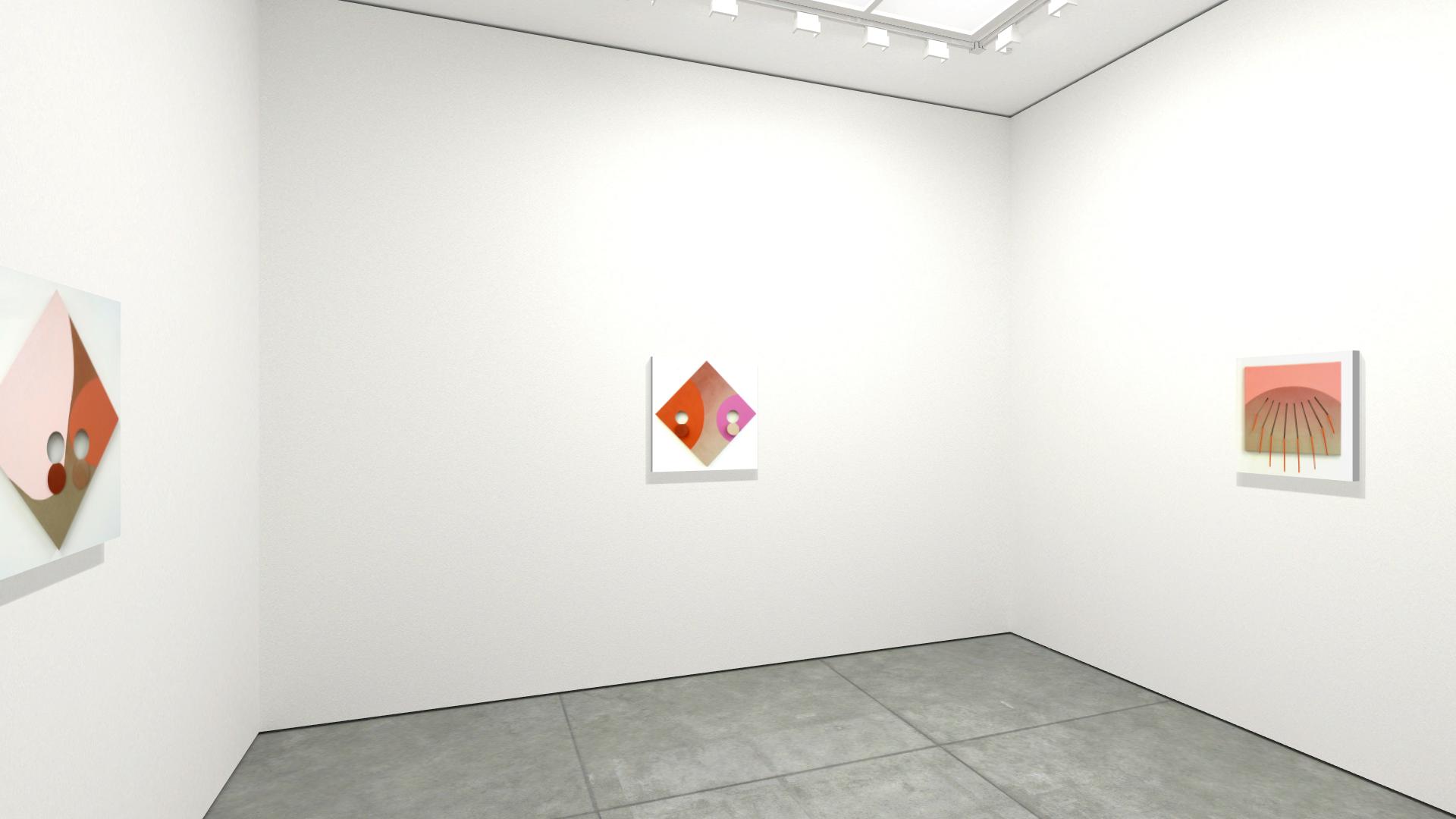

Linda King Ferguson is an artist whose career merges fine art with object making, exploring social and physical processes while her abstract work remains serene and meticulously constructed. Her new exhibition From the Center contains paintings in acrylic and stains on stretched linen.

The works make use of tilted orientations, bold colors, and the exploration of the substrate as a point of articulation. The series has something of the air of the Bauhaus, the Zero Group, and other artists who — not coincidentally — were concerned with applied art and interdisciplinary practice. Ferguson herself has had a career that winds through both design and fine art.

The immediate impression among these many paintings is one of playful abstraction, with almost Memphis group inspired designs. But a lingering impulse tells us to look deeper.

The surfaces of the paintings are often cut open, with material hanging out toward the viewer or absent completely. This gives the work one of its most telltale features — interrupting expectation and presenting a new kind of physicality.

We are so accustomed to the flat and whole canvas that the cut linen surface strikes us as a wound at first. And on a more animal level in the viewer, these can appear to be harrowing evidence of violence. The certainty of expectation is dismembered. This wound may be painted as well, the backside of the material presented to us as a part of the surface. It reminds us of the other side of the canvas that we so rarely see, the once hidden interior joining the show.

Consider Equivalence 44, where thin tendrils have been rent from the surface to precariously hang down, like fingers that reach beyond the lower border of the painting. The back of the linen surface is now facing us in aching red — an inflamed sibling of the soft pink that hovers at the top of the composition.

Once the viewer begins to reckon with how the artist is treating these effects, our interpretation moves from seeing these tendrils as dismemberment into something else entirely. We now see them as folds of a flower petal, as vestigial forms, as the protuberances of living bodies. It is evidence of the full activity and presence of a being no longer contrived as a two dimensional representation.

But by cutting through the canvas, Ferguson also cuts through one of the most unspoken yet sacrosanct beliefs in the realm of art: the painting as a window into another world. By allowing the gallery wall to peek out at you through the work, we are no longer fleeing our shared reality and escaping into the world of the painting. We are caught in our world. Despite our looking into the painting, we remain in the actual space of the gallery. We are still ourselves, milling about with others.

These works give us no cover, no escape. In this way, despite being abstract, they contain a social message in them. Especially today, where the undivided screen keeps our undivided attention, our minds are trained to constantly flee an embodied space into the virtual. In light of this, painting no longer has the luxury to let us escape, because we are now always in escape. The painting must now return us to a place, with feet on the ground and eyes open.

Rather than allowing us to be less present, From the Center presents looping circuits, always bringing us back into reality with greater force.

Ferguson has subverted the use of the painting to emphasize our shared world. After all, this is where things happen, where lives are lived, where histories are brought to bear and futures decided. It is art in objection to artifice.

And while there is this social content, there is also the purely aesthetic side of Ferguson’s paintings that engages us all on its own. The striking color masterfully establishes relationships between abstract forms, creating a certain kind of interior logic to the compositions.

In Equivalence 27, the orange and blue interact through erasure — an interesting way to describe the combination of complementary colors. The softened black field that surrounds these shapes acts as another kind of void. If we sit back and think about it, this painting contains two lacunae that are not only the absence of color but are also each other's opposites.

This is a strange reality being expressed, whether we recognize it or not. That these complicated relationships take place in a painting that can be taken as a cheerful addition to a modern setting makes its power all the more mysterious.

All of these features are brought together with visual cues borrowed from the feminine body. Ferguson uses this to ground her work in something easily felt, quickly related. It’s a move that allows the drama of a piece like Equivalence 85, with it’s echoing curve cutouts and hanging inversions, retain a relatability and even openness.

This inventory of shapes also prevents us from passing by unnoted, uninvolved, and ultimately unconcerned. Instead, the stakes of these paintings are the shared stuff of humanity, and Ferguson says as much by translating her visual language through the human form.

Ferguson received an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts and an MA from Rhode Island School of Design. She is the recipient of multiple awards, including development grants from the state of Michigan. Her work appears in many public and private collections, and she has shown in several selected and juried exhibitions.

Ferguson currently lives and works in Au Train, Michigan and Nashville, Tennessee, with occasional residence in Brooklyn, New York.

Jonathon M. Clark, independent critic